(Level B2+ The once celebrated and now forgotten Johann Kaspar Lavater of Zurich)

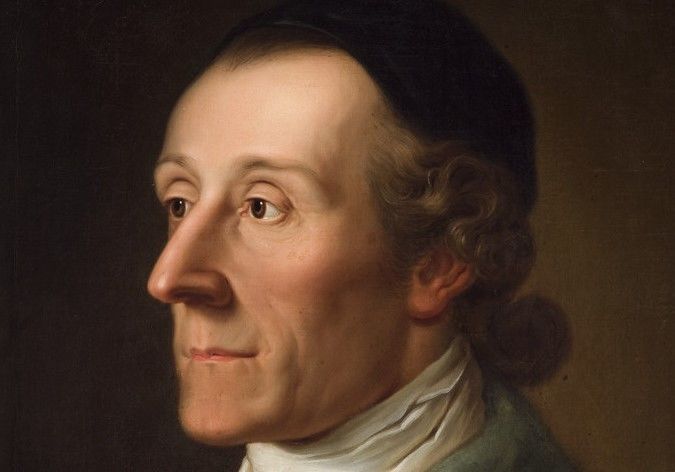

Swiss writer, poet, philosopher and pastor, Johann Kaspar Lavater (below), born in Zurich in 1741, was for much of his life one of the most celebrated men on the planet. He was visited by royalty, loved by Goethe, read rapturously and religiously around the world, feted by the great William Blake and an inspiration for writers such as Balzac, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy and Charlotte Bronte.

By Garry Littman, director of The Language House

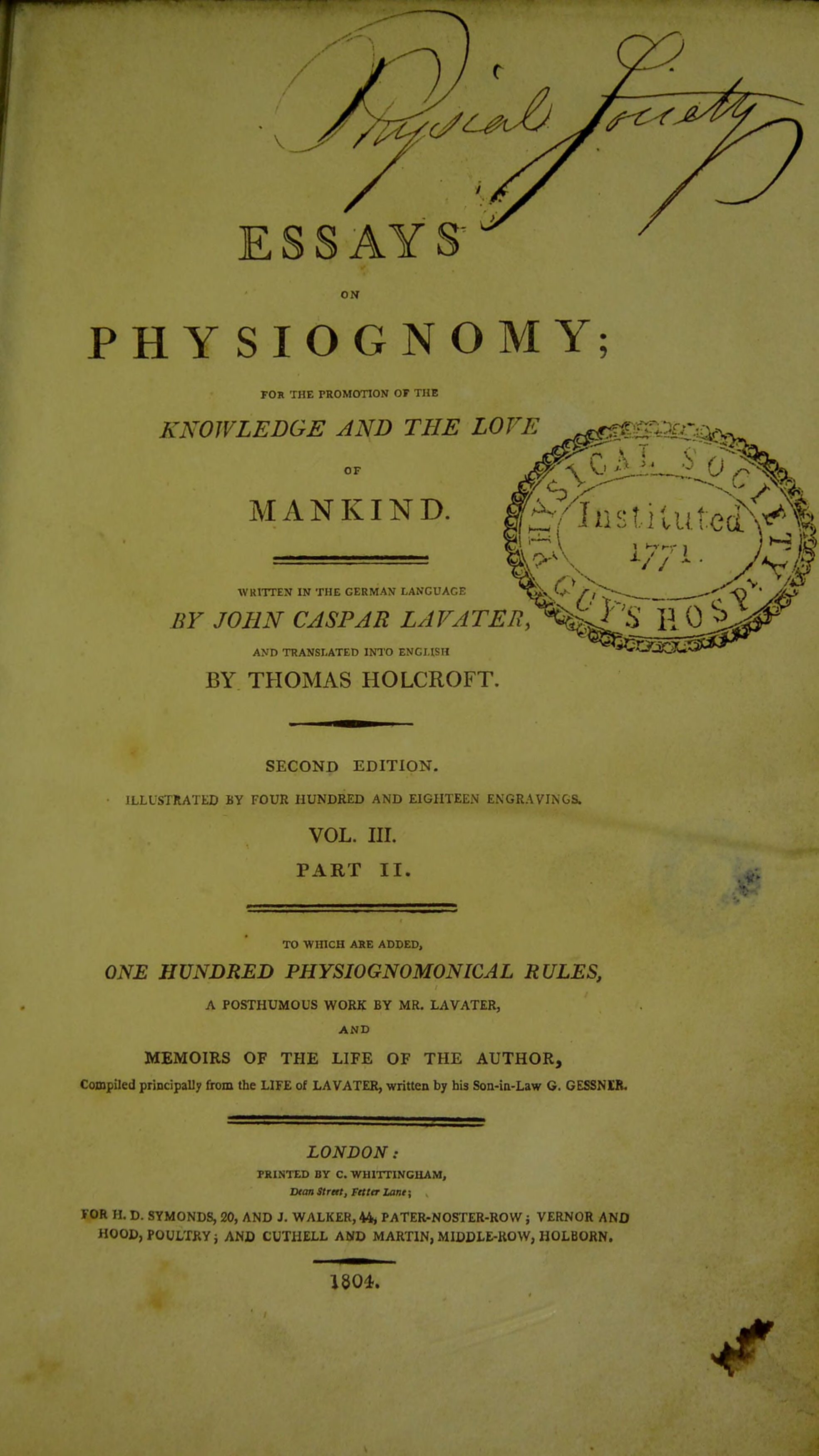

His enormously popular four-volume Essays of Physiognomy included engravings by Blake and was translated from German (15 editions), into French (16 editions), English (20 editions) as well as Russian, Dutch and Italian. The condensed version, ‘The Pocket Lavater’, was plagiarised, copied and reprinted all over the world. According to The Gentleman’s Magazine of London, Lavater’s work was “as necessary in every home as the Bible itself ”.

It was the ‘facebook’ of Enlightenment, and Lavater was its Zuckerberg from Zurich.

Johann Kaspar Lavater of Zurich

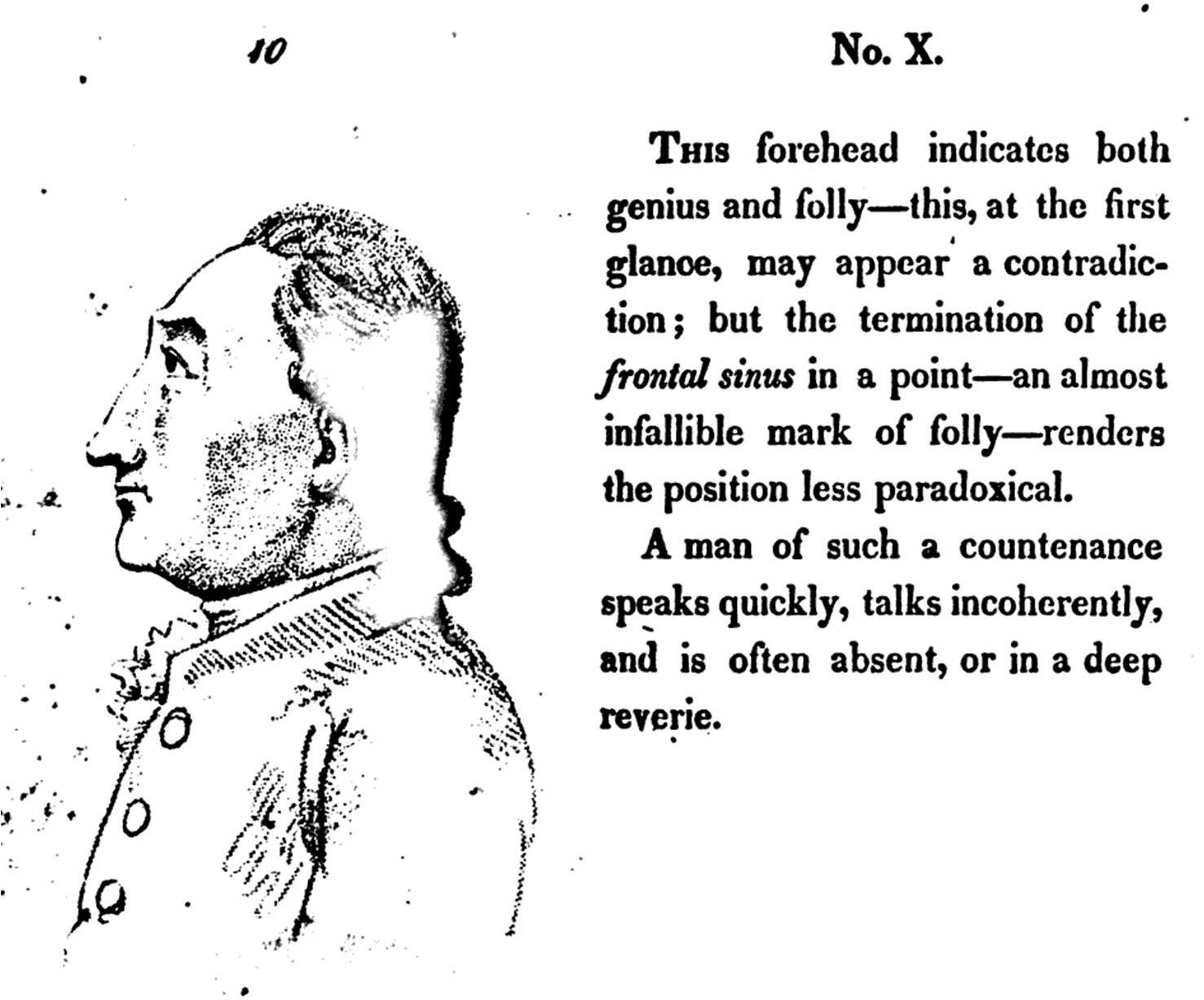

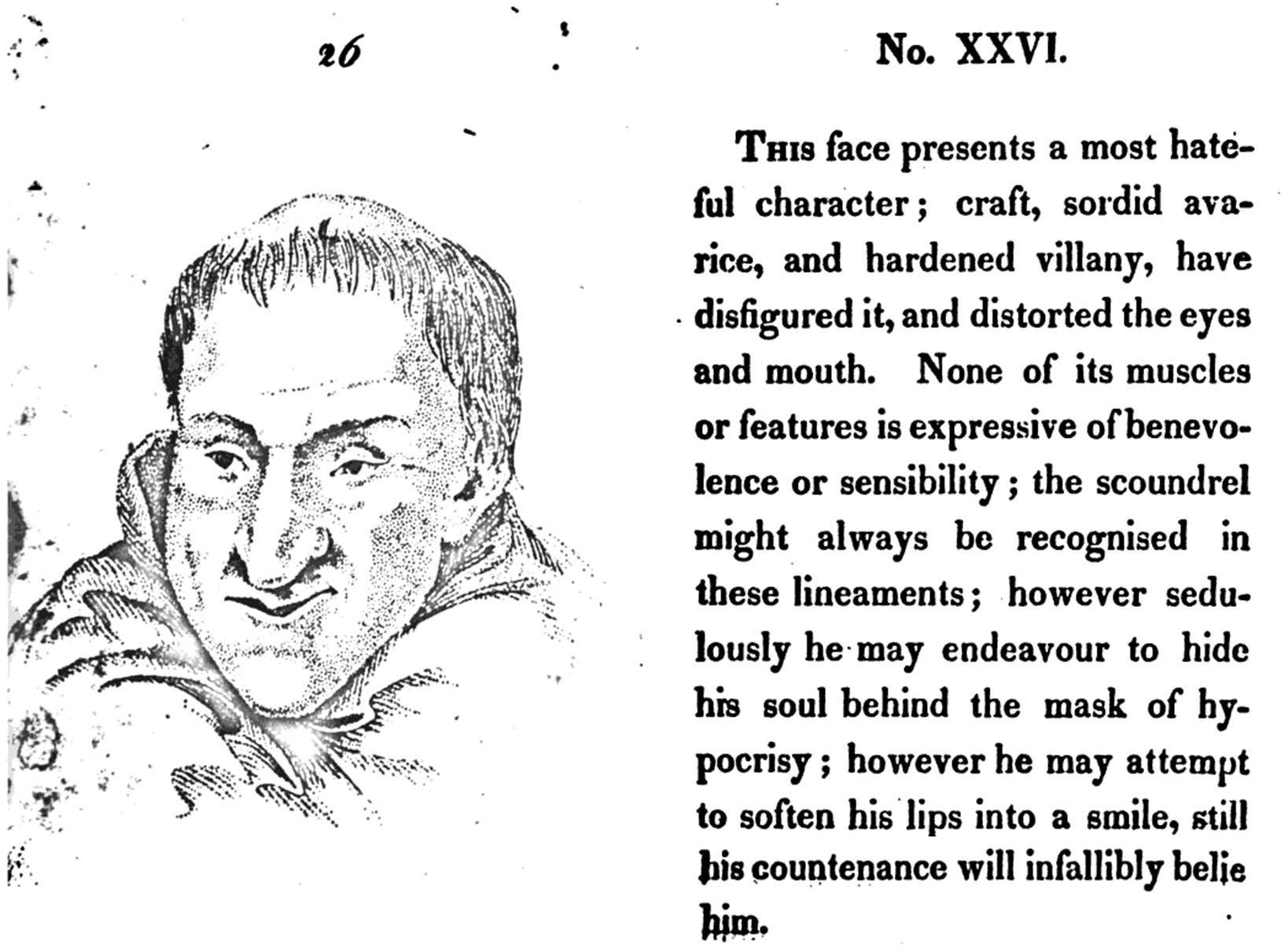

Lavater believed that facial features, such as the nose, forehead, lips and chin, clearly revealed mental abilities, character and emotional attitudes. He revealed this ‘science’ in hundreds of illustrations of faces accompanied by detailed and emphatic descriptions in his best-selling books.

Lavater’s ‘face book’ inspired legions of true believers who proudly called themselves Lavaterists .

“A servant would scarcely be hired until the inscriptions and engravings of Lavater had been consulted in careful comparison with the lines or features of the young man’s or woman’s countenance," The Gentleman’s Magazine wrote.

According to The Gentleman’s Magazine of London, Lavater’s work was “as necessary in every home as the Bible itself ”

Charles Darwin’s pre-voyage interview with Captain Robert Fitz-Roy of the HMS Beagle in 1831 almost ended in disaster. Why? Was it because of ill health or a physical handicap? No, it was because of the shape of his nose.

Darwin later wrote:

“Afterwards on becoming very intimated with Captain Fitz Roy, I heard I had run a risk of being rejected on account of the shape of my nose. He was an ardent disciple of Lavater, and was convinced he could judge a man’s character by the outline of his features, and he doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage”.

A young Charles Darwin with a nose lacking in energy and determination.

Each part of the face spoke to Lavater; the forehead, as well as the head shape, the eyes and the eyebrows, the nose, mouth, chin, cheeks and the hair.

"On a forehead light and joy reside; and also melancholy, anxiety, stupidity, ignorance, and perversity. It is the copper plate where the human feelings are carved by the fire ,” he wrote.

A high forehead indicated superior intelligence. Perpendicular wrinkles showed anger and horizontal wrinkles indicated ferocity. A lack of wrinkles revealed a cheerful and calm person. He classified the forehead into 31 sematic traits (sematic means conspicuous or warning signs).

"On a forehead light and joy reside; and also melancholy, anxiety, stupidity, ignorance, and perversity. It is the copper plate where the human feelings are carved by the fire ”

Each of these 31 traits corresponded to characteristics which were listed with references to tables, diagrams and faces. For example forehead description 7: ‘ An extremely protruding squared forehead,’ Lavater equated with a person of ‘extreme meanness, stupidity’.

Some of Lavater’s other foreheads were:

(13) A round forehead protruding at the top and straight in the bottom, perpendicular as a whole = intelligence, readiness, susceptibility, violence and coldness

(22) A forehead with curved contours, without angles = sweetness and adaptability

(28) A squared forehead whose lateral margins are very wide with very solid orbital arches = great prudence and great fidelity

(31) A front vein (the blue Y) in the middle of a wide wrinkle-free, well-curved forehead = extraordinary talent, enthusiasm and integrity

From the condensed and popular Pocket Lavater

Lavater took physiognomy to the extreme. He was inspired by 16 th century Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta , widely considered the father of physiognomy. Della Porta’s ‘ De Humana Physiognomia ,‘ theorised that people who look like particular animals would share those creatures’ traits (see below), an idea that sounds infantile and ludicrous today.

Lavater remained popular for much of the 19 th century, especially in England, before his work was widely criticised and relegated to pseudo-science. The expressions ‘stuck-up’ (a nose that bends slightly upwards), ‘thick-headed’, ‘high brow’ and ‘low brow’ come from Lavater’s work.

His physiognomy was based on the rather basic principle, that every shape made of straight lines refers to strength, rigidity, and intelligence and every shape made of curved lines is weakness, flexibility, and sensuality.

Lavater believed God’s perfection was visible in nature and the cover-page of his work has this wonderful dedication: ‘ Designed to promote the knowledge and love of mankind’ .

Critics said Lavater’s 'science' found deficiencies with anyone who was not male, a European or of Caucasian extraction.

Lavater was one of the lights of Enlightenment. However his candle burnt brightly and quickly. Physiognomy was tainted with prejudice, sexism and discrimination. Both Goethe and Blake initially adored and supported him, but later shunned him. Goethe accused him of superstition and hypocrisy and Blake later described him as superficial.

Critics said Lavater’s science found deficiencies with anyone who was not typically a European of Caucasian extraction.

Another wrote: “In vain do we boast that philosophy had broken down all the strongholds of prejudice, ignorance, and superstition; and yet, at this very time ... Lavater's physiognomy books sell at fifteen guineas a set”.

Lavater's theories strongly influenced art, literature, medicine, criminology and the emerging social sciences during much of the nineteenth century. The celebrated pastor from Zurich has been mostly forgotten, but his physiognomy continues to resurface in the most unlikely places.