Level C1 and above with vocabulary

The mother of all pandemics, the Black Death, or simply, the plague, killed an estimated 50 million people between the 14th and 17th century.

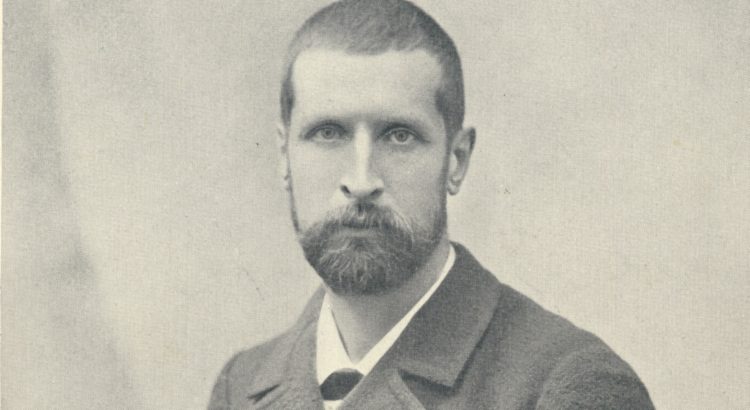

It was caused by a bacterium later identified and named Yersinia pestis, after a Swiss man born in canton Vaud; a brilliant, obsessive and eccentric bacteriologist.

His name was Alexandre Emile Jean Yersin.

Welcome to English in the Pandemic 10.

The right man, in the right place, at the right time

This is the story of the right man, in the right place, at the right time. Yersin was born in Lavaux near Aubonne in 1863 and studied literature in Germany and then medicine in Lausanne and Paris.

He was the youngest of four children. His Swiss father, a high school biology teacher died three weeks before Alexandre was born.

He was a curious and headstrong boy. At the age of eight, Yersin killed and dissected his mother’s cat and examined its organs under a microscope.

His passion was the growing study of bacteria and in 1886 he joined the celebrated French team of bacteriologists led by Doctor Louis Pasteur.

Yersin worked on the development of an anti-rabies serum and then joined the newly formed Pasteur Institute. There, Yersin and Dr Pierre-Paul Emile Roux proved that the diphtheria bacillus could cause the disease in animals, which led to the development of a vaccine against the deadly childhood disease.

By 1890, aged just 27, the brilliant bacteriologist

suddenly left his test-tubes and growing

reputation and jumped on a

ship bound for French Indochina

In 1889 Yersin became a naturalised French citizen.

By 1890, aged just 27, the brilliant bacteriologist suddenly left his test-tubes and growing reputation and jumped on a ship; destination French Indochina.

He led mapping expeditions, funded by the French government, into the wild uncharted mountains of Vietnam. It was here, as an explorer, far from the suffocating manners and politics of Parisian society, where this shy, socially reclusive, but tough and determined scientist was happiest. He was in his element in the mountainous jungle.

In May 1894, the plague resurfaced in the British colony of Hong Kong. The island government appealed for international help and the Pasteur Institute in Paris advised the island authorities that there was only one man for the job, and he was not far away. A week later, Yersin set sail from Saigon for Hong Kong.

Three days before he arrived the British authorities had warmly welcomed an older and more celebrated bacteriologist, the Japanese, Professor Kitasato Shibasaburō and his five assistants. The arrival of “the Professor” was front page news in the Hong Kong press and he and his entourage of doctors and scientists were feted by the British administration.

There was little fanfare for Yersin.

He was an oddity.

The authorities gave him hospital space and equipment, access to corpses of plague victims and most importantly, political favour.

There was little fanfare for Yersin. He was an oddity. He was only 31, a maverick, a man who lacked and detested the mannerisms of high society, a man who spoke fluent Vietnamese, but little English, and a man who had emerged from the jungles of Vietnam. He was referred to disparagingly as “The Frenchman”.

Edward Marriott recounts in his book, The Plague Race (Picador 2002), the disastrous meeting of the world’s two leading bacteriologists in the middle of the Hong Kong plague. Their common language was school student German. Yersin clearly imagined the two would work in collaboration. His offer was met with ridicule.

Marriott writes:

“Barely had Yersin finished his stumbling open remarks in German that the Japanese scientists, without a cursory response, began ‘laughing among themselves’, and then, to a man, they turned their back to him.”

Yersin was further humiliated when requests for access to the morgue were turned down numerous times. The authorities considered him somewhat of a pest.

“The Japanese have bribed the staff

at the hospital so they

that will not provide

me with any bodies for autopsy”

“The Japanese have bribed the staff at the hospital so that they will not provide me with any bodies for autopsy”, Yersin complained to his mother in a letter.

The Vaudois and his unlikely aide and translator, an Italian priest, Bernardo Vigano, who was twice his age, befriended and then bribed two guards of the island’s overflowing mortuary. They paid them a fee for each bubo, the horrible, often black swellings in the thighs, neck, groin or armpit glands which Yersin carefully sliced from the corpses inside the dark foul-smelling morgue.

He then needed a place to work. Again, the British authorities were focused on the professor and had little interest or time for Yersin’s requests.

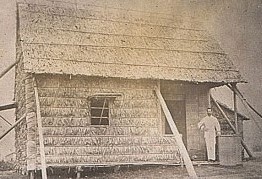

Yersin outside his laboratory-residence

Undeterred, Yersin paid a Chinese builder to build him a paillotte, a large hut made of bamboo and timber with a roof and walls of grass and with enough space for a laboratory and room for a bed. It took just 24 hours to construct. At one end was a small veranda which looked onto the hospital where Professor Kitasato and his team were at work with the full support of the island administration.

The quest to find the bacillus had become more than a race to save lives. It was a race for scientific and historic recognition. Kitasato was perfectly placed and impatient to add another distinction to his exemplary career. He was an ambitious man. Within days he had announced to the world and perhaps more importantly, the prestigious Lancet Medical and Science Journal, that he has isolated the bacillus much to the delight and accolades of the world science community. Within a week he packed up his laboratory and left the island.

In hindsight, he was too hasty and a little blinded by ambition and his own self-importance. His description of the bacillus was imprecise and his cultures were found to be contaminated.

The Vietnamese authorities awarded

him the revered title

of the nation’s ‘Fifth Uncle’

Yersin was the first person to accurately describe the plague pathogen.

“The pulp of the buboes always contains short stubby bacilli,” he noted in one of the most important papers ever written about human disease.

Yersin named the bacillus Pasteurella pestis, after his mentor, Louis Pasteur. In 1944, it was given a newly defined genus, Yersinia.

Electron microphotograph of a mass of Yersinia pestis bacteria in the stomach of the flea vector

Yersin was part of the French team which developed the first anti-plague serum. This was perfected and produced in Yersin’s laboratory in Nha Trang in Vietnam in 1895, which became a part of the Pasteur Institute.

In 1933, he was made an honorary president of the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The Vietnamese authorities awarded him the revered title of the nation’s Fifth Uncle.

He died in his adopted country in 1943 at the age of 80. His home became a museum and shrine and given the title, Lau Ông Năm, Home of the Fifth Uncle.

His tombstone says: “Benefactor and humanist, venerated by the Vietnamese people.”

Reading and reference:

The Plague Race, Edward Marriott (Picador); The Great Mortality, John Kelly (Harper Perrenial); Alexandre Yersin (1863-1943): Vietnam’s “Fifth Uncle”, Singapore Medical Journal.

Vocabulary:

Check the meanings of the words in red bold in the text. Match the words with their definitions. Check your answers below.

- suffocating manners

- tough

- disparagingly

- oddity

- pest

- bribe (verb)

- overflowing

- foul-smelling

- undeterred

- too hasty

- blinded by ambition

- shrine

a. more than full

b. a place of worship like a temple

c. to speak about something or someone in a way that suggests that it or they have little importance or value

d. strong, able to manage difficult conditions or situation

e. an annoying person or thing

f. used to describe the behaviour of high society in Paris. Yersin couldn’t breathe or relax in high society.

g. to give somebody money or something valuable in order to persuade them to help you, especially by doing something dishonest

h. disgusting and horrible smell

i. when you do not allow obstacles or problems stop you from doing something

j. done very quickly, often with a bad result

k. when you are so focused on getting a result that will make your famous that you do not see important things or information around you

l. a person or thing that is strange or unusual and doesn’t belong

Answers:

1.f 2. d 3.c 4.l 5.e 6.g 7.a 8.h 9.i 10.j 11.k. 12.b